Beyond the Blueprint: Contextual Architecture in Burleigh Heads & Gold Coast

Architecture transcends mere building; it involves storytelling, evoking emotion, and respecting cultural heritage. A crucial element often separating mundane structures from meaningful places is context. For our Burleigh Heads architectural practice, designing with context – understanding a project’s unique Gold Coast setting – elevates architecture beyond simple aesthetics and function.

Good architecture is like a tree—it cannot exist in isolation from its soil. Its roots must reach deep into the physical, cultural, and historical context of its place to truly flourish.

A context-sensitive approach fosters connections between a building, its surroundings, and its users, leading to more resilient, sustainable, and engaging spaces. It enriches lives and cultivates a sense of belonging.

This article explores the essential aspects of context – physical, social, cultural, and historical – and discusses how architects integrate these elements to create enduring architecture that celebrates human experience.

Contextual Architecture

Contextual architecture is design that responds meaningfully to its surroundings rather than existing in isolation. It considers multiple layers of context—from physical site conditions to cultural narratives—creating buildings that belong to their place and time while enhancing the existing environment.

What is Context in Architectural Design?

In architecture, context encompasses the interwoven layers influencing a building’s design:

Physical Context

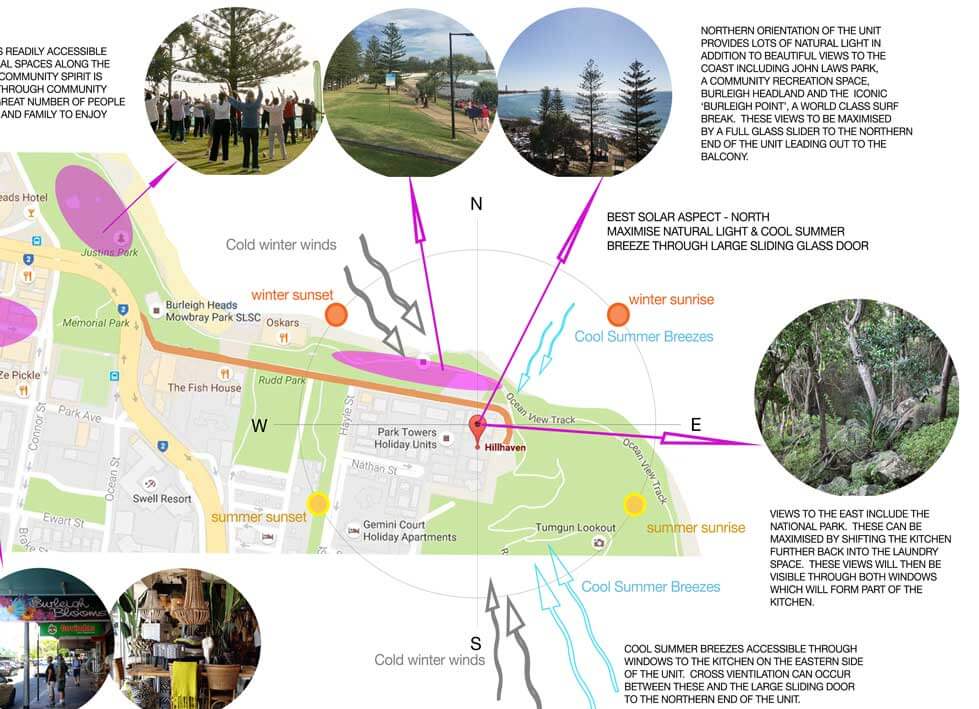

The tangible environment – topography, climate, vegetation, solar orientation, surrounding structures. Site analysis informs form, materials, and orientation, aiming for harmony with the landscape and optimizing energy performance and comfort. How does the building respond to Gold Coast sun, breezes, and storms?

Social Context

The needs, values, and activities of the people who will use the space and the wider community. Understanding demographics and local preferences helps architects design spaces that foster interaction, inclusivity, and a sense of belonging.

Cultural Context

The traditions, customs, aesthetic values, and identity of a community or region. This includes prevalent architectural styles, local construction techniques, or significant narratives. Incorporating these elements creates buildings that resonate culturally and contribute to a distinct sense of place.

Historical Context

The stories, events, and architectural evolution that have shaped a location over time. Understanding a site’s history helps architects make informed decisions about preservation, adaptation, or thoughtful contrast with existing structures.

Comprehensive site analysis reveals multiple layers of context that inform design decisions, from topography and climate to cultural and historical factors.

The Benefits of Context-Responsive Design

Environmental Performance and Sustainability

Climate-Responsive Design: Buildings designed with their climate in mind perform better environmentally and economically. In Queensland’s subtropical conditions, this means designing for natural ventilation, solar control, and storm resilience.

Site-Specific Solutions: Understanding unique site conditions leads to innovative solutions. A sloping coastal site might suggest elevated structures that capture breezes and views while minimizing site disturbance.

Resource Efficiency: Local materials and traditional techniques often represent the most sustainable choices, having evolved specifically for local conditions.

Social and Cultural Benefits

Tip

Research by environmental psychologist Roger Barker demonstrates that well-designed contextual environments can significantly improve social interaction, community cohesion, and individual well-being by creating familiar yet inspiring spaces.

Sense of Place: Contextual design creates environments that feel authentic and meaningful to their users and communities.

Cultural Continuity: Respecting and interpreting local traditions helps maintain cultural identity while allowing for contemporary expression.

Community Engagement: Involving local stakeholders in the design process ensures projects serve actual community needs.

Economic Value

Long-term Performance: Context-responsive buildings often require less mechanical intervention, reducing operational costs.

Market Appeal: Properties that respond to their context tend to have stronger market appeal and better resale values.

Tourism and Identity: Distinctive, place-based architecture can become a community asset that attracts visitors and investment.

Strategies for Contextual Design in Gold Coast Practice

Site Analysis and Research Methodology

Our systematic approach to site analysis combines quantitative environmental data with qualitative cultural and historical research to inform design decisions.

Our contextual design process begins with comprehensive site analysis:

Environmental Mapping:

- Solar studies and microclimate analysis

- Topographical surveys and soil conditions

- Vegetation patterns and ecological relationships

- Water movement and drainage patterns

Cultural Research:

- Historical documentation and archival research

- Community stakeholder interviews

- Local building tradition analysis

- Regulatory and planning context review

Neighborhood Character Study:

- Architectural style documentation

- Street pattern and public space analysis

- Scale and proportion relationships

- Material and color palette observation

Material Selection and Local Resources

Regional Material Palette:

- Queensland hardwoods with proven coastal performance

- Local stone and aggregate for site-specific expression

- Contemporary materials that complement traditional choices

Sustainable Sourcing:

- Prioritizing locally-sourced materials to reduce transportation impacts

- Supporting regional suppliers and craftspeople

- Specifying materials with established local maintenance networks

Cultural Appropriateness:

- Understanding the cultural significance of material choices

- Respecting traditional construction techniques while embracing innovation

- Ensuring accessibility and affordability for the local community

Scale and Proportion Strategies

Neighborhood Scale Integration

New buildings should contribute positively to the existing urban fabric. This doesn’t mean copying existing structures, but rather understanding the underlying patterns that create neighborhood character—such as setbacks, height relationships, and rhythm of openings.

Height and Massing:

- Responding to existing neighborhood scale patterns

- Creating transitions between different building types

- Maximizing views and privacy for all properties

Street Interface:

- Designing appropriate relationships between public and private space

- Contributing to pedestrian-scale environments

- Supporting existing commercial and social patterns

Case Study Applications in Burleigh Heads Context

Coastal Residential Projects

Our approach to coastal residential design demonstrates contextual principles:

Site Positioning:

- Elevated structures responding to flood zones and coastal weather

- Orientation for optimal cross-ventilation and solar control

- Landscaping that supports indigenous coastal vegetation

Architectural Expression:

- Contemporary interpretation of Queenslander proportions and details

- Material choices that weather gracefully in salt air

- Indoor-outdoor living spaces that celebrate coastal lifestyle

This Burleigh Heads residence demonstrates how contemporary design can honor traditional Queensland coastal architecture while meeting modern lifestyle requirements.

Mixed-Use Development Considerations

Urban Context Integration:

- Ground floor activation supporting existing commercial patterns

- Upper level setbacks maintaining neighborhood scale

- Parking and service integration that doesn’t dominate street frontages

Community Benefit:

- Public space contributions that enhance neighborhood amenity

- Affordable housing components addressing local housing needs

- Infrastructure improvements that benefit the broader community

Challenges and Opportunities in Contextual Practice

Balancing Innovation with Respect

Creative Interpretation vs. Literal Copying: The most successful contextual architecture interprets rather than copies historical precedents, finding contemporary expressions of enduring principles.

Technology Integration: Modern building systems and smart home technology can be seamlessly integrated while maintaining contextual appropriateness.

Changing Lifestyles: Contemporary family structures and work patterns require flexible spaces that traditional models may not provide.

Regulatory and Economic Constraints

Important

Planning regulations don’t always support the most contextually appropriate design solutions. Successful contextual practice often requires patient community engagement and clear communication of design benefits to regulatory authorities.

Planning System Navigation:

- Building strong relationships with local planning authorities

- Clearly documenting design rationale and community benefits

- Proposing innovative solutions within existing frameworks

Cost Management:

- Demonstrating long-term value of contextual design decisions

- Finding cost-effective ways to achieve contextual goals

- Prioritizing the most impactful contextual elements within budget constraints

The Future of Contextual Design Practice

Climate Change Adaptation

Resilient Design Strategies:

- Designing for increased storm intensity and flood risk

- Adapting traditional passive cooling strategies for changing temperatures

- Planning for sea level rise and coastal erosion

Ecosystem Integration:

- Supporting biodiversity through building and landscape design

- Creating carbon sequestration opportunities

- Managing stormwater and water quality improvement

Digital Tools and Analysis

Advanced Modeling:

- Computational fluid dynamics for microclimate analysis

- Daylighting and solar analysis for optimal environmental performance

- Community engagement through virtual reality and 3D modeling

Cultural Documentation:

- Digital archives of local building traditions

- Community story mapping and oral history integration

- Ongoing post-occupancy evaluation and learning

Conclusion: Architecture as Cultural Stewardship

“Each building is a living thing, which can only be alive to the extent that it is connected to the stream of life around it.”

Contextual architecture represents more than a design methodology—it’s an approach to cultural stewardship that honors the past while creating meaningful spaces for contemporary life. In our Burleigh Heads practice, we’ve found that the most successful projects emerge from deep engagement with place, community, and environmental conditions.

The challenge and opportunity for contemporary architects lies in interpreting these contextual relationships through innovative design solutions that address current needs while respecting cultural heritage. This requires patience, research, community engagement, and a willingness to find creative solutions within existing constraints.

As our communities face increasing environmental and social challenges, contextual design offers a path toward more resilient, sustainable, and meaningful architecture. By grounding our practice in place-based knowledge and community relationships, we can create buildings that not only serve their immediate users but contribute to the long-term cultural and environmental health of our region.

Interested in contextual design for your Gold Coast or Burleigh Heads project? Contact our team to discuss how place-responsive architecture can enhance your project’s environmental performance and cultural significance.

References

Alexander, C. (1979). The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford University Press.

Barker, R. G. (1968). Ecological Psychology: Concepts and Methods for Studying the Environment of Human Behavior. Stanford University Press.

Frampton, K. (1983). Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance. In H. Foster (Ed.), The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture (pp. 16-30). Bay Press.